Travelling on the Edge

- Mar 12, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: May 24, 2023

Tarusha Mishra, Action Researcher at HumanQind

It was one of the first of its kind of meetings in our project school in the New Delhi district, an all-girls government school, where the school’s principal, a few teachers, a school alumna pursuing an MBA, and an 11-year-old girl named Khushi (name changed) came together to discuss making their school zone safe for all school community members. She made a remark that would compel one to think about the hardships students face in their everyday commute to school:

“I don’t like walking on my school street. My friends and I don’t get space to walk on the street. We can’t walk on the footpaths because they are broken and full of garbage. The only option left is to walk on the edge of a high-speeding road”

As per OECD’s Conceptual Learning Framework for student agency, in a system that encourages student agency, learning involves instruction, evaluation, and co-construction. However, with the current systems of education, the relationship between students in school and school teachers and authorities remains transactional. Students are being acted upon, rather than working themselves, they are being shaped rather than shaping their realities, and they are accepting decisions and choices determined by others for them, rather than making their own decisions¹.

As established by Khushi’s anecdote and statistics which say that children die on road every day² ³, their safety in their daily commute to school becomes not just a public health concern, but an integral determinant of children flourishing in their urban environment. An intervention in making schools a safer zone for students thus became a much-needed entry point into addressing these concerns.

Intervention: Student leading the way with co-design

CROSSWALK, a student-led innovative approach towards empowering and training school authorities to physically implement solutions that promote safer infrastructure, active mobility and better management of school traffic circulation entailed the Safe School Zone program. The following two approaches to codesign helped in shaping an experience of participation and citizenship for the students:

Community Mobilization & Leadership

In a pioneering initiative, a Road Safety Club was formulated wherein children shared equal decision-making power on the table with adults. As a result of deeply engaging with the students, co-designing with them, and building capacities in them to share power with adults, the students understood the importance of demonstrating leadership and bringing their voice into matters that concern them.

Human-centred design

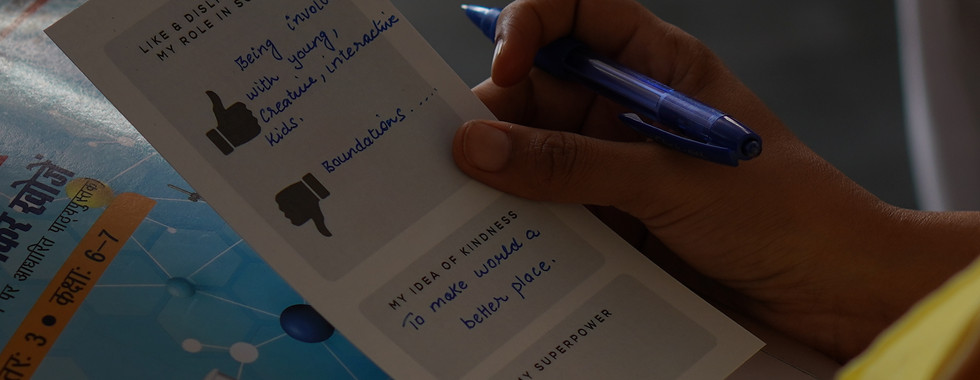

The engagement with students followed a child-centred approach. Children of 11 years of age were given a voice in decision-making through a human-centred design thinking curriculum. It comprised 9 workshops that enabled them to co-design pressing issues related to their school zone safety. As a result, a safe school zone management blueprint was prepared by the school community rendering equity, compassion and justice to the school community.

Results

The Crosswalk curriculum paved the path of voice and visibility in 3 steps:

Activating citizenship

Reimagining their built environment provided students to approach their surroundings with new possibilities. While what was an everyday affair, or business as usual for them, was now being seen with a critical approach. The inaccessible footpaths and life-less streets were identified as issues that the student wished to change. Safety, cleanliness and looking at the school street as a public space emerged as some of the key points in initial brainstorming sessions, for humans and beyond human experience for community animals in the school street. By realising their power of voice to bring a change, students began to understand their role as equal citizens in cities.

Empowering action

Becoming aware of their human rights as road users helped students to design their school street keeping in mind the needs of their community, a community that included considerations for younger students, mothers, students with disabilities, parents and teachers of old age and the community animals. Through the power of co-creation, students transformed their ideas, thoughts and wishes into a street model called ‘Rainbow Dream’, thereby demonstrating the creativity and sense of community already inherent in them.

Catalysing change

Drawing inspiration from examples of child leaders like Greta Thunberg, students understood that change is possible, and age certainly can’t become a barrier to it. Their intent that was realised through the power of stories helped them to strategise taking their codesign model to the entire school community, even to students from the neighbouring schools.

Challenges and limitations

A few challenges encountered during the project were not just at an operational level- like the availability of required infrastructure and alignment with school calendars but also stemmed from the deep-rooted issues persisting in society. When the students in the class were once complimented as ‘smart girls’ for their responses, a girl hesitantly asked, “ma’am, aren’t only boys supposed to be smart?” During their workshop interactions, girls also shared about how their freedom of mobility is compromised, which isn’t the case they see with boys in society. Such anecdotes reflect the concern of seeded gender stereotypes and the need to actively promote a gender-equal, respectful, non-violent culture with gender-aware pedagogy amongst students, teachers and other staff members in schools. If not addressed properly, schools and other educational institutions can implicitly legitimise and reinforce harmful gender norms⁴.

The Way Forward

After co-designing their own school street, the way forward for this particular class from school would be to take the project to all the school community members, i.e., all school students and staff members, local government authorities, neighbouring school staff and students and people of the neighbourhood. Collecting basic travel data and information on the socio-emotional state of each student in school would encompass their collective viewpoint, providing the impetus to decision-making authorities at the school and governance level to bring about necessary interventions identified in the project by students. While shifting the needle from the current state of student commute would require several short and long-term efforts, the lived reality of students from walking on the edge to flourishing in their built environment would only be achieved through a community-oriented approach.

References 1. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/student-

agency/Student_Agency_for_2030_concept_note.pdf

2. https://www.thestatesman.com/india/childrens-day-30-children-witness-crash-commute-school-

1503024526.html

3. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/31-children-die-in-road-crashes-in-india-every-

day/articleshow/78808958.cms 4. https://cdn.sida.se/publications/files/-gender-based-violence-and-education.pdf

Comments